Mesopotamia, located in the region now known as the Middle East, encompasses parts of Southwest Asia and lands around the eastern Mediterranean Sea. It is part of the Fertile Crescent, an area often referred to as the “Cradle of Civilization” due to the numerous innovations that emerged from the early societies in this region, which are among the earliest known human civilizations on Earth.

The word “Mesopotamia” derives from ancient Greek words: “meso,” meaning between or in the middle of, and “potamos,” meaning river. Situated in the fertile valleys between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, this region is now home to modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, Turkey, and Syria.

THE AGE OF THE SUMER EMPIRE

4000 BCE – 2000 BCE

The Sumerians, emerging around 4000 BCE, are considered one of the oldest known civilizations in the world. They lived in Southern Mesopotamia between 4000 BCE and 2000 BCE and laid the foundations for subsequent civilizations, contributing significantly to cultural and intellectual heritage.

The Sumerians are credited with the development of the first writing system and advances in medicine, astronomy, mythology, religion, mathematics, and diplomacy. They also introduced cultural elements such as the Christmas tree decoration, wedding rings, evil eye beads, sorcery, fortune-telling, and legends like the Creation and Flood.

The Structure of Sumerian City-States and Diplomacy

The Sumerians organized themselves into autonomous city-states, numbering around 35, each governed by a unified monarchical structure. This political organization played a crucial role in the development of diplomacy among the Sumerians. Rather than facing external enemies, these city-states often conflicted and formed alliances among themselves, which enhanced their diplomatic interactions.

Each city-state was ruled internally by an administrator called Ensi or Patesi, while foreign policy was overseen by a city council that held the powers of Ensi in check. A notable example is Gilgamesh, the mythical king of the city of Uruk, who consulted the council of elders regarding actions against the city of Kish. In the absence of a decision for war from the elders, he convened a new assembly of the city’s youth to make a war decision .

Diplomatic Records and Military Strategy

A series of inscriptions document the conflicts and alliances within the Sumerian city-states, providing the oldest diplomatic records of Sumer and, by extension, Mesopotamia. Samuel Noah Kramer, a prominent Sumerologist, analyzed these records and referred to the text describing the relations between Uruk King Enmerkar and the Kingdom of Aratta (in Western Iran) as a “silent diplomatic war.” According to Kramer, this text represents the oldest instance of “psychological warfare” in history.

Due to frequent internal conflicts, each Sumerian city-state maintained a powerful, full-time, professional army to defend its territory. The Sumerians primarily pursued a defensive policy rather than an aggressive expansionist strategy, guided by the proverb, “You go and conquer the enemy’s country, they will conquer yours” .

The Sumerians made significant advancements in military technology, understanding that a well-equipped army provided a crucial advantage. Unlike other states of the period that used copper and stone, the Sumerians used bronze to craft armor and weapons. They invented the first known chariots in history. However, over time, the Sumerians shifted from citizen armies to hiring mercenary Akkadian soldiers. This reliance on mercenaries eventually led to their downfall, as these soldiers ceased serving the Sumerian state, overthrew the government, and established their kingdom.

THE AGE OF THE AKKADIAN EMPIRE

2350 BCE – 2334 BCE

After the Sumerians, the Akkadians, who were part of the Semitic-speaking peoples, emerged in Mesopotamia between 2350 and 2334 BCE. The Akkadians are believed to have migrated to Mesopotamia around 3000 BCE and initially engaged in farming and animal husbandry within the Sumerian city-states. Over time, they assumed significant roles in city administration, serving as mercenaries in the Sumerian army and as clerks in city temples.

Taking advantage of the declining influence of the Sumerian Empire, the Akkadians, under the leadership of Sargon of Akkad, established their own empire and made “Agade” (Akkad) their capital.

By the legendary narrative of Akkad, Sargon, or Sargon of Akkad, is purportedly depicted as the trusted advisor and emissary of Ur-Zababa, the reigning monarch of Kish, one among the prominent Sumerian City-States. Allegedly perceiving Sargon’s burgeoning ambition and ascendancy as a threat to his own sovereignty, King Ur-Zababa purportedly devised a stratagem to neutralize him, entrusting Sargon with the delivery of a missive to his adversary, King Lugal-zagesi of Uruk. The contents of this missive, as purportedly relayed, explicitly mandated the execution of the bearer upon delivery. Perceiving the imminent peril orchestrated against his person, Sargon allegedly took decisive action, preemptively eliminating King Ur-Zababa and subsequently seizing control of the realm.

This narrative, deeply entrenched in ancient Mesopotamian lore, postulates Sargon’s seminal role as an early exemplar of diplomatic and ambassadorial agency, imbued with the capacity to navigate intricate political machinations and assert authority within the prevailing socio-political milieu. Within the annals of historical conjecture, Sargon’s purported actions exemplify a pivotal juncture wherein diplomatic agency, ostensibly wielded as a tool of statecraft, precipitated a radical reconfiguration of governmental authority, marking a notable departure from conventional modes of succession and governance within the ancient Near East. As such, this legend not only serves as a testament to the enduring fascination with the figure of Sargon but also offers a nuanced lens through which to apprehend the intersection of diplomacy, ambition, and power within the formative epochs of human civilization.

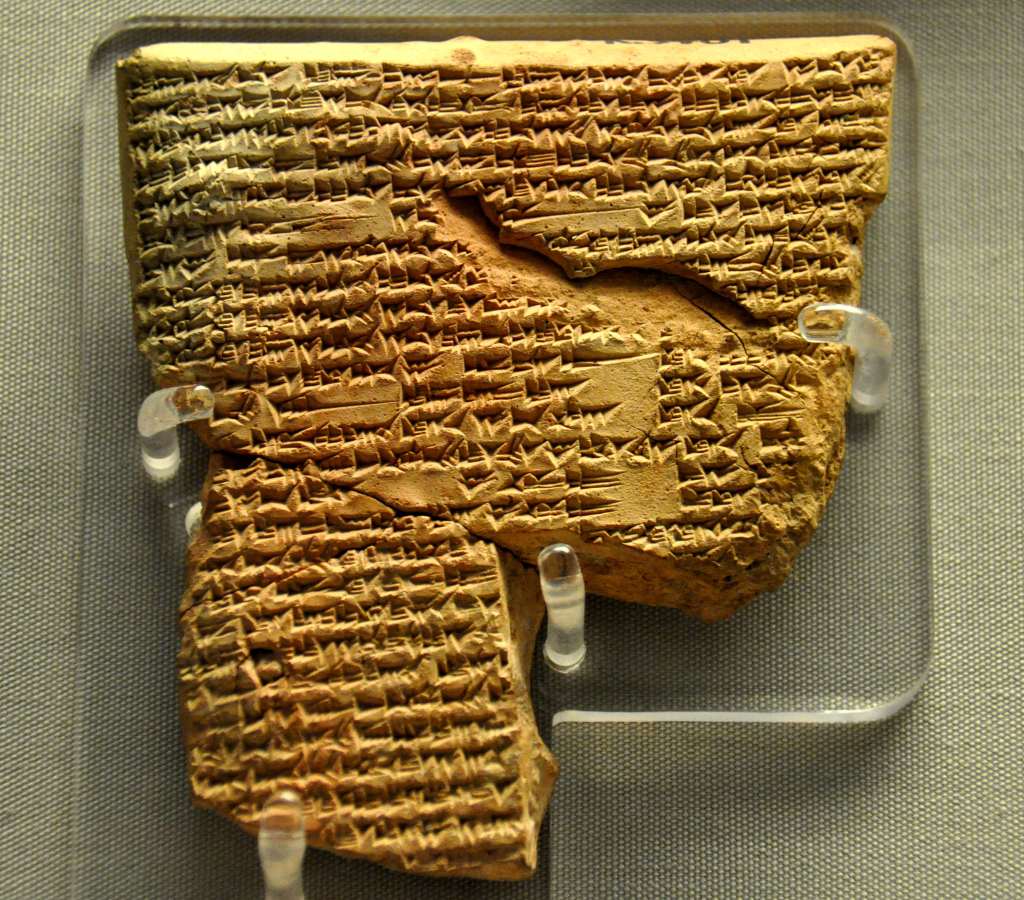

(Photo: Story of the birth of Sargon, early 2nd millennium BC)

Establishment of the Akkadian Empire

In contrast to the Sumerian city-state system, the Akkadians established an absolute monarchy with a central government, creating the first significant kingdom and empire in world history. Their strong military, organized as the first regular army in history, enabled them to exert influence over Mesopotamia and Anatolia, and even conduct expeditions as far as Magan in the Arabian Peninsula. This expansionist policy necessitated a more sophisticated form of diplomacy.

One of the Akkadians’ most significant contributions to diplomacy was the establishment of a common diplomatic language. The Akkadian language, spoken in the Babylonian and Assyrian regions, became the lingua franca of Mesopotamia. This common language facilitated diplomatic correspondence not only within Mesopotamia but also with neighboring regions.

Decline and Fall of the Akkadian Empire

After the death of the last king, Shar-Kali-Sharri, several individuals declared themselves kings, leading to internal turmoil. During this period, King Dudu (2189 – 2168 BCE) and King Shu-Turul (2168 – 2154 BCE) emerged as prominent figures. King Dudu fought against the Gutians, nomadic people from the Zagros Mountains who dominated the Babylonian region, but he was ultimately defeated. The Akkadian Empire, reduced to a small territory in Middle Babylon under King Shu-Turul, was eventually destroyed by the Gutians in 2154 BCE.

The Gutians established their own dynasty, the Guti Dynasty1, and dominated the region for nearly a century, marking the end of the Akkadian Empire’s influence.

- The Gutis were nomadic people who lived in the Zagros Mountains (Southern Mesopotamia). They destroyed the Akkadian Empire and established the Sumerian Guti Dynasty. They have dominated the region for nearly a century.

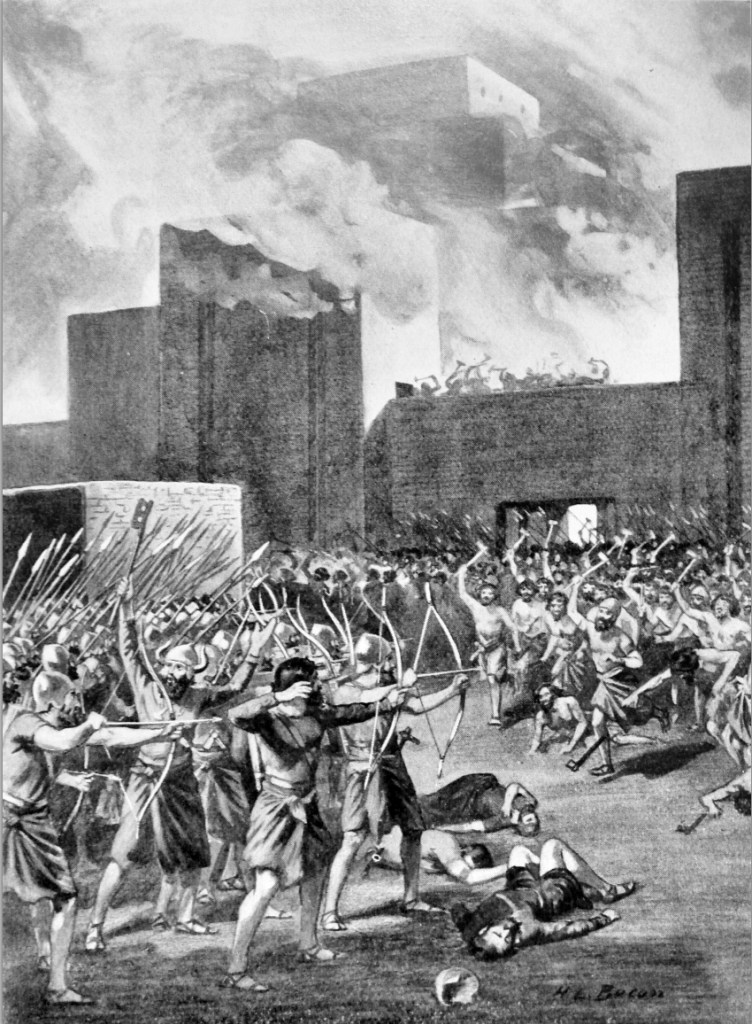

The Gutians capturing a Babylonian city, as Akkadians are making a stand outside their city.

H.L. Bacon (died in 1948) – History of the Nations, published in 1915

THE AGE OF THE BABYLONIAN EMPIRE

1894 BCE – 539 BCE

The Babylonian Empire, believed to have been founded around 1894 BCE near the city of Babylon (south of present-day Baghdad), played a crucial role in Mesopotamian history. Initially a modest city within the Akkadian Empire, Babylon rose to prominence and power under the leadership of Hammurabi, the Amorite ruler. This transformation made Babylon one of the most powerful empires in the region.

The diplomacy of the Babylonian Empire can be examined in three distinct periods:

- Pre-Hammurabi Period

- Hammurabi Period

- Post-Hammurabi Period

Pre-Hammurabi Period

During the Pre-Hammurabi Period, Babylon was relatively weak and constantly seeking allies to counter the threat posed by the influential Sumerian city-state of Larsa in the south. To strengthen its position, Babylon formed an alliance with Mari, a city located in present-day Syria. Archaeological excavations have unearthed a letter archive that includes official and unofficial correspondence between the two states, as well as intelligence reports gathered by spies.

Despite being allies, the kings of Babylon and Mari kept a close watch on each other through espionage. One notable letter found in Mari reveals that a Mari spy had risen to the position of counsellor in Hammurabi’s court, reporting all palace activities to his king. The alliance was solidified through pacts stipulating mutual military support: “If the enemy attacks you, my ships and troops will support you, but if the enemy attacks me, then your ships and troops will unite with me” (Klengel, 2002: 57-58).

Hammurabi Period

During the first 25-30 years of Hammurabi’s reign, Babylon’s diplomatic relations were meticulously maintained. However, as Babylon grew stronger and eventually conquered Larsa, its diplomatic stance began to change. Reports from Mari indicated a shift in Babylon’s attitude, with envoys protesting the denial of their ceremonial attire at the Babylonian court, which signaled a diplomatic slight. Hammurabi allowed them to don their ceremonial clothes but asserted his authority over such matters, eventually forbidding foreign ambassadors from wearing honorific clothing.

This diplomatic crisis strained relations between Babylon and Mari, leading to a symbolic rupture. Soon after, Babylon declared war on Mari and incorporated it into its empire, demonstrating the shifting dynamics of power and diplomacy.

Post-Hammurabi Period

After Hammurabi’s death, Babylon weakened, entering a period of decline under his successor. In the 18th century BCE, increasing numbers of Kassites migrated to Babylon. The Babylonians, aiming to avoid conflict, sought to ally with the Kassites. A Babylonian tablet records an ordinance to prepare 300 pitchers of beer to welcome Kassite ambassadors, indicating diplomatic efforts to foster friendly relations.

However, the Babylonian state continued to weaken, culminating in its invasion by the Hittites in the early 16th century BCE. The Hittites destroyed the Hammurabi dynasty, creating a power vacuum that the Kassites exploited to take control of Babylon. The Kassites ruled Babylon for about 400 years but eventually succumbed to Assyrian invasions. In 1155 BCE, Babylon fell under Assyrian rule.

THE AGE OF THE ASSYRIAN EMPIRE

2025 BCE – 612 BCE

The Assyrian Empire, often referred to simply as Assyria, emerged as a dominant force in Mesopotamia during the decline of the Babylonian Empire, existing from approximately 2025 BCE to 612 BCE. Like other ancient civilizations in the region, the Assyrians were of Semitic origin, with their capital initially established in the city of Aššur and later in Nineveh. Known for their aggressive policy of conquest, the Assyrians expanded their territory significantly, subjugating Babylon in the south, Urartu in the north, and various other kingdoms including Ras Shamra, Yamhad, Damascus, Hama, and Israel. At the height of their power, Assyrian rulers took on the grandiose title of “king of Assyria, Babylon, Sumer and Akkad, all over the world.”

Assyrian Diplomacy and Military Strategy

Assyrian diplomacy was heavily influenced by their military prowess and expansionist agenda. They maintained detailed records, including a vast collection of documents that provided insight into their interactions with other Near Eastern civilizations. The archives are notably extensive, with 25,000 clay tablets from the library of King Assurbanipal (669-627 BCE) alone. These records introduce us to various peoples for the first time, such as the Medes and Persians in the 9th century BCE and the Arabs as desert-dwelling tribes.

Assyrian kings documented their military campaigns and the severe punishments inflicted on their enemies in these records. For example, an Assyrian yearbook recounts the brutal tactics used against foes: “I crushed 3000 sword fighters of the enemies. I took away their works, their goods, their oxen and cattle. I burned most of the captives. I cut off some of their hands and arms. I cut off their noses and ears. I’ve had most of their eyes gouged out. I made a pile of the severed heads of their dead. I burned their teenage daughters and sons. I have destroyed their city” (Finkelstein, 2012: 65-66). These vivid accounts highlight the ruthless nature of Assyrian military and diplomatic strategies, which often aimed to intimidate and demoralize their adversaries.

Relations with Babylon

Despite their conquests, the Assyrians recognized the Babylonian state as their equal, allowing it semi-autonomous rule under Assyrian-descended rulers. Babylon remained a significant center of science and culture. However, internal and external provocations, notably from the Elamites and Arameans, incited Babylonian rulers to rebel against Assyrian dominance. Assurbanipal managed to quell these revolts, but his successors struggled to maintain control.

The alliance between Babylon and the Medes marked a significant turning point in the region’s diplomacy. This coalition considered the first “multinational alliance agreement” in history, was solidified by the marriage of Babylonian prince Nebuchadnezzar to a Median princess. This alliance successfully captured Nineveh in 612 BCE, leading to the division of the Assyrian Empire between Babylon and the Medes.

The Fall of Assyria

One of the most notable aspects of Assyria’s final years was the unexpected support it received from Egypt, a former adversary. Egypt, which had suffered under Assyrian rule, chose to back Assyria against the Babylon-Median alliance. Despite Egyptian military support, the Assyrian state could not withstand the combined forces of Babylon and the Medes. Defeated in 605 BCE, the remnants of the Assyrian troops sought refuge in Egypt. Ultimately, the Assyrian Empire’s reliance on brute force and intimidation proved unsustainable. The Medes and Babylonians thoroughly destroyed Assyrian cities, temples, and homes, ensuring nothing of the empire remained.

With Assyria’s collapse, Babylon experienced a brief resurgence, though it did not regain its former glory. The power dynamics in Mesopotamia shifted, leading to the rise of Iranian peoples. Cyrus the Great (Kurash), who ruled Babylon from 559 to 530 BCE, marked the end of Semitic dominance in the region, ushering in a new era under Persian control.

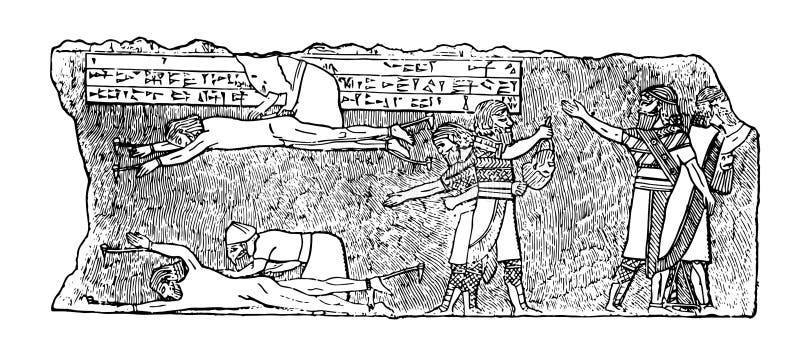

The image shows Assyrians Flaying Prisoners Alive. It is also called as colloquially known as skinning. It is a slow and painful method of execution in which the skin is removed from the body, vintage line drawing or engraving illustration

Leave a comment