DIplomacy In the AncIent EgyptIan CIvIlIzatIon:

A ComprehensIve Study

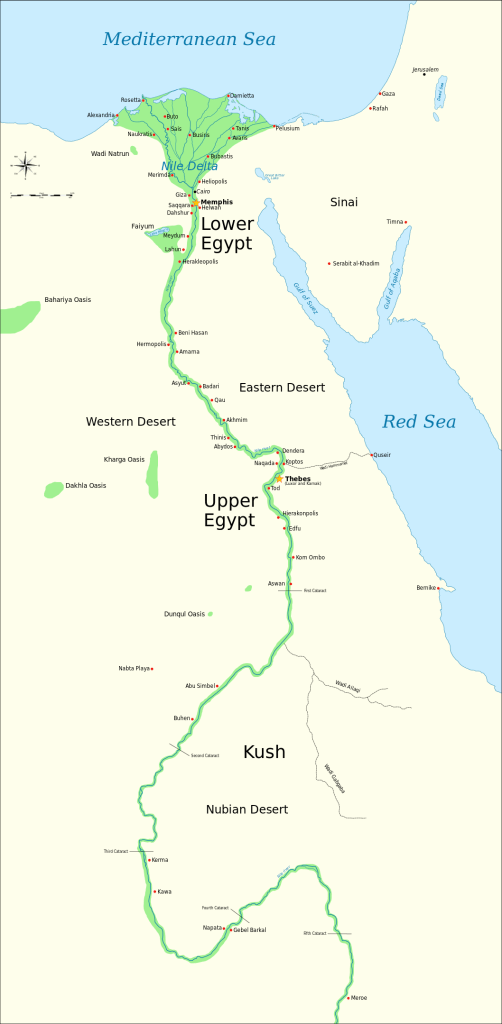

The Ancient Egyptian Civilization, one of the cradles of human civilization, emerged along the fertile banks of the Nile River. This river, originating from Lake Victoria and dividing into three branches—the White Nile, the Blue Nile, and the Atbara River—was revered by the Egyptians as a deity due to the abundance and life it provided. This paper delves into the origins, political structure, and unification of Ancient Egypt, highlighting the key figures and theories that shaped its early history.

The Nile River, referred to by the ancient Egyptians as a god, was central to the development of their civilization. Its annual floods deposited rich silt along its banks, creating fertile land ideal for agriculture. This abundance enabled the growth of a complex society that, until 3150 BC, was divided into two distinct regions: Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt.

Lower and Upper Egypt: Early Political Structure

Before the unification, Egypt was characterized by a lack of central governance. The civilization was divided into Lower Egypt, encompassing the Nile Delta and the northern delta region where the Nile flows into the Mediterranean Sea, and Upper Egypt, which extended from Nubia in the south to the Nile Delta in the north. These regions were independently ruled by different leaders, whose exact identities remain shrouded in mystery.

The rulers of Lower Egypt are known primarily from the Palermo Stone, also referred to as the “Royal Chronicles.” While many names remain vague, some tangible references have survived. In contrast, Upper Egypt was divided into twenty-two administrative regions known as Ta Shemau, or the Land of Reeds. The rulers of Upper Egypt, identified through hieroglyphs, include enigmatic figures such as “Finger Snail,” “Fish,” “Stork,” “Elephant,” “Bull,” and “Scorpion.” Among them, “Scorpion I” is considered the first significant ruler.

The Palermo Stone, the fragment of the Egyptian Royal Annals housed in Palermo, Italy

- Title: Abhandlungen der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften aus dem Jahre ..

- Contributing Library: Smithsonian Libraries

The Unification of Egypt

The unification of Lower and Upper Egypt is attributed to King Narmer, a pivotal figure in ancient Egyptian history. Narmer is believed to have ruled around 3100 BC, establishing the First Dynasty of Ancient Egypt (3050 BC – 2890 BC) and becoming its first Pharaoh. However, the exact nature of his ascendancy remains a topic of scholarly debate.

One prevailing theory suggests that Narmer was a direct successor of Scorpion I, thus bridging the political divide between the two regions. According to another theory, Narmer himself was the Scorpion King, marking the transition from the so-called Dynasty 0 to the First Dynasty. This theory is supported by new archaeological findings, which continue to shed light on this formative period in Egyptian history.

Narmer’s Reign and Legacy

Narmer’s reign marked the beginning of a centralized state, which persisted for nearly three millennia. Despite occasional periods of fragmentation, the political unity established by Narmer was largely maintained until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 31 BC. This unification allowed Egypt to develop a cohesive cultural and political identity, which became one of the most enduring in ancient history.

Geographical Isolation and Development

Ancient Egypt, one of the world’s earliest and most enduring civilizations, developed along the Nile River’s fertile banks. This civilization, covering approximately 1500 kilometres along the Nile’s 6,853-kilometer course, was remarkably self-contained. Flanked by the river and vast deserts, Egypt’s geographical setting fostered a unique insularity.

Ancient Egypt’s geographical isolation was a significant factor in its development. With the Nile River on one side and expansive deserts on the other, Egypt was naturally insulated from external influences. This isolation was both a blessing and a curse. It allowed for the flourishing of a unique and stable civilization but also limited Egypt’s interactions with neighboring cultures.

Egyptian scholars of the time viewed the Nile’s south-to-north flow as the natural order, perceiving rivers that flowed in the opposite direction as anomalies. This perspective further reinforced their isolationist mindset. Unlike other ancient civilizations that established port cities and developed naval fleets, Egypt did not create a port on the Mediterranean shore where the Nile emptied. Consequently, Egypt lacked a significant naval presence, limiting its maritime interactions.

The Nile’s surrounding environment was far more hospitable than today’s arid landscape. Verdant gardens and tall palm trees flourished along the riverbanks, giving way to savannahs and grasses as one moved inland. This abundance facilitated a prosperous society engaged in fishing, riverine transport, agriculture, animal husbandry, mining, and trade in the desert’s rich mineral resources. The wealth of the Egyptian community is epitomized by the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza, the most magnificent testament to their prosperity.

Military Vulnerability and Foreign Influence

Despite its wealth, Ancient Egypt lagged behind other contemporary civilizations in military technology. The Egyptians’ reliance on bronze and iron weapons rendered them vulnerable to better-equipped adversaries. This vulnerability was starkly demonstrated during the Hyksos invasion. The Hyksos, foreign tribes migrating via Syria, managed to conquer and rule Egypt for nearly a century. This period of foreign domination highlighted the limitations of Egypt’s isolationist policies and the need for military and political reform.

The expulsion of the Hyksos marked a turning point in Egyptian history. The traumatic experience of foreign rule prompted the Egyptians to reconsider their insular approach. Determined to prevent future invasions, they began to engage more actively with the outside world. This shift in policy was particularly evident during the New Kingdom Period (1500-1100 BC), a time of significant military expansion and diplomatic activity.

The New Kingdom Period: Expansion and Diplomacy

The New Kingdom Period saw Egypt transform from a relatively insular society into a dominant power in the Near East. Pharaohs such as Thutmose I led military campaigns that extended Egypt’s influence into the Syria-Palestine region. These conquests brought numerous small kingdoms under Egyptian control, establishing Egypt as the preeminent power of the region.

However, Egypt’s rise to dominance also brought it into conflict with other major powers, notably the Mitanni. To avoid a protracted and costly war, both Egypt and Mitanni sought a diplomatic resolution. This diplomacy was epitomized by the marriage of Pharaoh Thutmose IV to a Mitanni princess, symbolizing an alliance between the two powers. This diplomatic marriage was part of a broader trend in which Pharaohs married foreign princesses, integrating them into the royal harem. Interestingly, while foreign princesses frequently became consorts, Egyptian princesses were never sent abroad as brides, reflecting a unique aspect of Egyptian royal protocol. For instance, Pharaoh Amenhotep III (also known as Amenophis III) famously refused the Babylonian king’s request to marry an Egyptian princess, asserting, “No Egyptian Pharaoh’s daughter has been released since ancient times.”

The Age of Amarna: Revolution and Restoration in Ancient Egypt

The Age of Amarna marks a distinctive and tumultuous period in Ancient Egyptian history, characterized by the radical religious reforms of Pharaoh Akhenaten. The 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt witnessed significant developments under the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III and his successor, Akhenaten. Akhenaten, originally named Amenhotep IV, initiated profound changes that diverged sharply from traditional Egyptian practices. This period, known as the Age of Amarna, is notable for its religious, political, and cultural transformations, culminating in Akhenaten’s establishment of the Aten religion and the construction of a new capital city, Tel el-Amarna. This paper explores the motivations behind these changes, their impact on Egyptian society, and the subsequent efforts to erase Akhenaten’s legacy.

Akhenaten’s Religious Revolution

Upon his ascension to the throne, Amenhotep IV adhered to the polytheistic traditions of his predecessors. However, in the fifth year of his reign, he adopted the name Akhenaten, meaning “servant of Aten,” and introduced a monotheistic worship centred around the deity Aten. This shift represented a radical departure from the entrenched polytheistic system, where the god Amun held preeminence. Akhenaten’s religious reforms included the prohibition of traditional religious practices, the destruction of temples dedicated to other gods, and the promotion of Aten as the sole deity.

This theological upheaval had profound implications for Egyptian culture and society. By dismantling the traditional religious institutions, Akhenaten disrupted the socio-economic structures that had long supported them. The priesthood of Amun, a powerful and wealthy institution, was particularly affected, leading to widespread resistance and discontent.

The Establishment of Tel el-Amarna

In conjunction with his religious reforms, Akhenaten relocated the capital from Thebes to a new city, Akhetaten (modern-day Tel el-Amarna). This move was partly motivated by a desire to break free from the entrenched power of the Amun priesthood in Thebes and to create a city dedicated solely to Aten. Tel el-Amarna, situated on previously untouched land, was notable for being one of the first planned cities in history. Its layout reflected Akhenaten’s religious vision, with temples and public buildings dedicated to the worship of Aten.

Despite its innovative design, Tel el-Amarna’s existence was short-lived. Akhenaten’s reign lasted approximately 15-17 years, and following his death, the city was abandoned, and its structures were dismantled. The subsequent rulers, eager to restore traditional religious practices, erased Akhenaten’s name from monuments and records, referring to him as the “enemy pharaoh.“

The Amarna Letters: Diplomatic Correspondence

One of the most significant archaeological discoveries from this period is the Amarna Letters, a collection of clay tablets unearthed by British and German archaeologists in the late 19th century. These tablets comprise diplomatic correspondence between the Egyptian administration and its counterparts in the Near East. The Amarna Letters provide invaluable insights into the political landscape of the time, highlighting Egypt’s interactions with various vassal states and neighbouring kingdoms.

The letters reveal a complex web of relationships, including alliances, conflicts, and diplomatic negotiations. Notably, the language and tone of the correspondence varied depending on the recipient. For instance, letters to the Babylonian kings were written in the Babylonian language and addressed the recipient as “my brother” or “my friend,” reflecting a sense of equality and mutual respect. In contrast, correspondence with the Syrian principalities, which were subordinate to Egypt, often employed more hierarchical language, with the Pharaoh being addressed as “my sun, the sun of my heaven, my master, my god.”

Left Image: EA 161, letter by Aziru, leader of Amurru (stating his case to pharaoh), one of the Amarna letters in cuneiform writing on a clay tablet.

Right Image: Five Amarna letters on display at the British Museum, London

Cultural and Political Implications

Akhenaten’s radical reforms had far-reaching consequences for Egypt. The suppression of traditional religious practices and the concentration of resources on the new capital strained the economy and alienated many segments of society. The destruction of temples and religious artifacts disrupted the cultural continuity that had defined Egypt for centuries.

After Akhenaten’s death, the reactionary measures taken by his successors underscored the extent of the discontent his policies had generated. The rapid dismantling of Tel el-Amarna and the restoration of polytheism signified a return to traditional values and the reestablishment of the old order. This period of restoration culminated in the reign of Tutankhamun, who played a pivotal role in reasserting the authority of the Amun priesthood and re-aligning Egypt with its historical religious practices.

Ancient Egypt, once a beacon of cultural and economic prowess, faced a gradual decline beginning in the late Bronze Age. The collapse of the Hittite Empire in the 12th century BC marked the start of Egypt’s increasing vulnerability to external threats.

The Collapse of the Hittite Empire and Its Aftermath

The Hittite Empire’s collapse around 1200 BC significantly altered the power dynamics in the Near East. As one of Egypt’s key allies, the Hittites had provided a counterbalance to the rising Assyrian threat. Without this alliance, Egypt found itself increasingly exposed to external aggression. The Assyrians, emboldened by the absence of Hittite power, began to assert their dominance in the region.

In response to these changing geopolitical circumstances, Egypt initially sought a path of neutrality. However, this strategy proved untenable as the Assyrian Empire expanded. The destruction of the Kingdom of Israel by the Assyrians in the 9th century BC forced a shift in Egyptian foreign policy. The influx of Israelite refugees seeking protection further complicated Egypt’s position, ultimately leading to direct military confrontation with the Assyrians.

The Assyrian Invasions and Egypt’s Subjugation

In 674 BC, the Assyrian king Esarhaddon launched a significant military campaign against Egypt. Although the Assyrians did not establish full control over Egypt, they imposed substantial war reparations and installed Psammetichus I as a vassal ruler. This period marked Egypt’s second subjugation by a foreign power, the first being the Hyksos invasion centuries earlier.

Psammetichus I’s reign under Assyrian oversight was characterized by attempts to assert greater independence. After a few years, he declared Egypt’s autonomy from Assyrian control. However, this declaration of independence did not translate into long-term stability. In an effort to bolster Egypt’s military capabilities and economic position, Psammetichus I introduced significant reforms, including the use of Greek mercenaries and the granting of economic concessions to foreign traders.

Economic Policies and Cultural Exchange

The integration of Greek mercenaries into the Egyptian army introduced significant cultural and economic changes. Greek soldiers, merchants, and settlers established a presence in Egypt, leading to the creation of the colony of Naukratis. This settlement became a hub of Greek trade and culture within Egypt, symbolizing the increasing foreign influence on the Egyptian economy.

The economic policies of Psammetichus I, aimed at revitalizing Egypt’s trade and economy, ultimately led to greater foreign dependence. The granting of capitulations allowed foreign traders, particularly Greeks, extensive privileges in the Egyptian market. Over time, these policies eroded Egypt’s economic independence, making it vulnerable to external economic pressures.

Political Instability and Foreign Dependence

As Egypt’s economy became increasingly tied to foreign trade, political instability grew. The reliance on Greek mercenaries in the military and the establishment of foreign colonies within Egypt created internal divisions and weakened the traditional power structures. Additionally, the influx of Jewish refugees and the establishment of a significant Jewish colony at Elephantine further diversified Egypt’s population and added to the complexity of its social fabric.

The political fragmentation and economic dependency left Egypt ill-prepared to face new external threats. The rise of the Persian Empire in the 6th century BC presented a formidable challenge that Egypt not withstand. In 525 BC, the Persian king Cambyses II conquered Egypt, marking the end of its sovereignty and the beginning of Persian rule.

Leave a comment