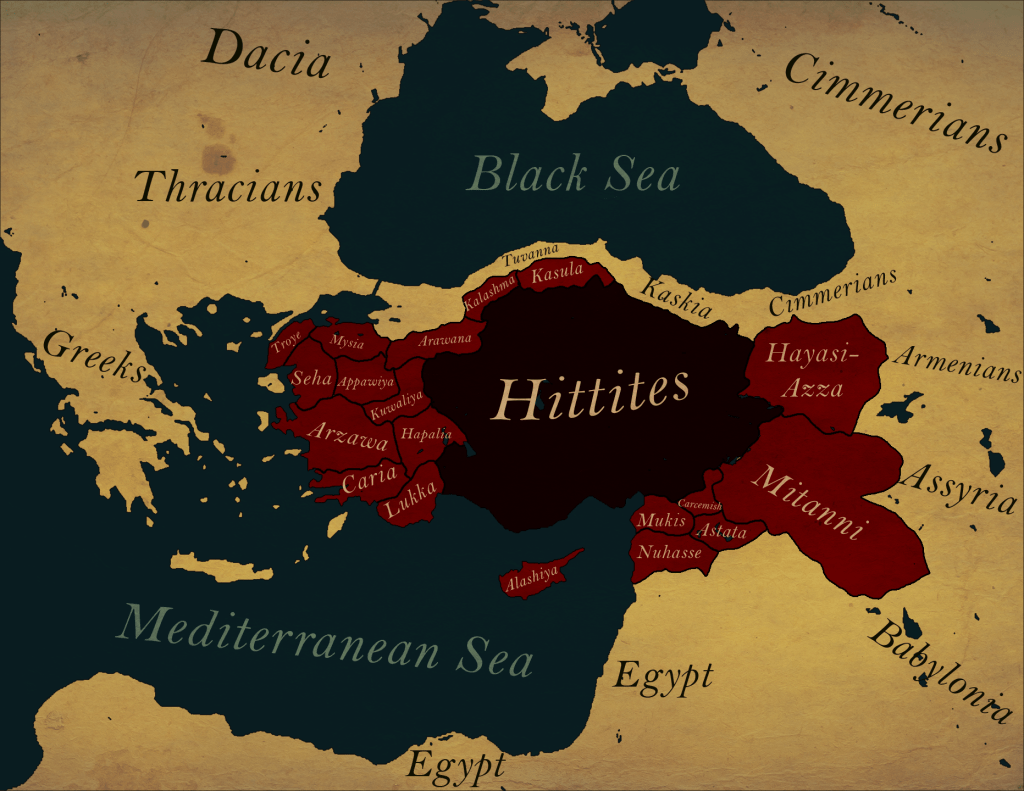

The Hittites, who established the Hittite Empire in Hattusha around 1600 BC, played a pivotal role in the diplomatic history of the ancient Near East. The Hittites, also referred to as the Etiler, are believed to have descended from the Hatti people who inhabited Anatolia prior to the arrival of the Nesa people, now recognized as the Hittites. This dual identity has led to some confusion in early Hittitology. The Hittites spoke and wrote in Hittite and Luwian, both belonging to the Anatolian branch of Indo-European languages. These languages represent some of the earliest examples of Indo-European languages in written form. Additionally, the Hittites adopted Sumerian and Akkadian for diplomatic correspondence, demonstrating their linguistic adaptability.

Archival Practices and Neutral Historiography

The Hittites were meticulous in their record-keeping, maintaining detailed diaries known as “Anal” or “chronicles”. These diaries served to account for their gods, documenting wars, treaties, and daily activities with remarkable impartiality. The Hittite chronicles are considered reliable sources due to their straightforward language and the belief that any falsehoods would incur divine punishment. This practice marks the Hittites as pioneers of neutral historiography, offering valuable insights into their history and culture.

Early Diplomatic Engagements

The Hittites first appeared in historical records through Assyrian merchant reports in the 18th century BC. These accounts reveal a thriving trade relationship, with the Hittites importing woven goods and tin from the Assyrians and exporting gold and silver. This exchange facilitated cultural assimilation, including the adoption of cuneiform writing.

In their diplomatic endeavors, the Hittites balanced military conquests with conciliatory policies. For instance, during the reign of Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC) in Egypt, the Hittites sent envoys to declare their loyalty, despite Egypt’s regional dominance. Similarly, in their interactions with the Kizzuwatna Kingdom, the Hittites negotiated treaties to resolve border disputes, exemplifying their preference for peaceful resolutions.

Diplomatic Treaties and Language

The Hittites’ diplomatic documents often employed egalitarian language, as evidenced by treaties with neighboring states. A notable example is the treaty with Kizzuwatna, which outlined reciprocal obligations for the return of subjects who crossed borders. The language used in these treaties reflected mutual respect and equality, a practice that changed only when the Hittites achieved dominance over their counterparts.

“If the servants of the Great King (Hittite King) migrate with their women, goods, cattle, sheep and goats and enter Kizzuwatna, Paddatissu (Kizzuwatna King) will capture them and return them to the Great King. If the servants of the Great King (Kizzuwatna King) migrate with their women, property, cattle, sheep and goats and enter the land of Hatti, Paddatissu (Kizzuwatna King) will capture them and return them to the Great King. “

As it can be understood from what is written, both sides used an identical way of addressing and diplomatic language. Unfortunately, this equality-based address and diplomatic language disappeared when the Hittites dominated Kizzuwatna.

Trade and Internal Policies

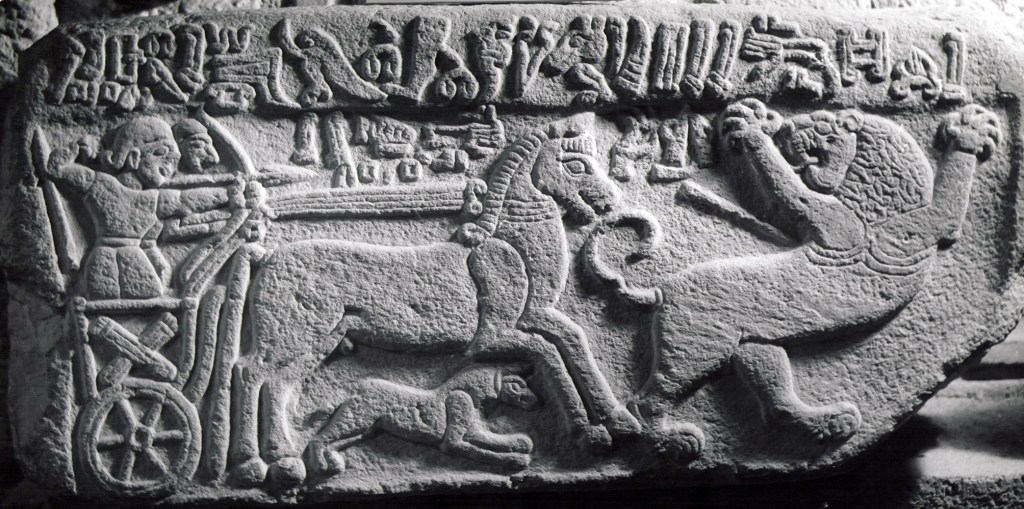

The Hittite kings prioritized the safety and prosperity of their subjects, regardless of origin. They implemented measures to protect trade routes and compensated traders for losses, imposing harsh penalties on perpetrators. This approach contrasts with the more ruthless policies of contemporary Assyrian rulers. Even in conquest, Hittite kings often sought peaceful resolutions. For example, Mursili II (1272-1268 BC) refrained from destroying the Kingdom of Seha after its queen personally appealed for mercy.

“I would destroy them (the King of Seha and his people). However, he sent his mother to meet me. The woman fell on my knees and said, “Lord, don’t destroy us; take us under your protection.” As the woman came to greet us and fell on my knees, I could not stand it and did not march on the land of Seha.”

Mursili II (1272-1268 BC)

Decline and Fall

By the end of the 2nd millennium BC, irregular migrations and invasions destabilised Anatolia, exacerbating the Hittite Empire’s internal challenges. The death of Suppiluliuma II marked the end of political unity in Hittite lands. The empire’s demographic changes and economic difficulties, compounded by external pressures, ultimately led to its dissolution. The Hittite Empire faded into history, leaving behind a legacy of diplomatic innovation and cultural exchange.

Leave a comment