Ancient Greece, the cradle of Western civilization, is also the birthplace of diplomacy as a formalized practice. The complexity of Greek diplomacy is epitomized by two key terms: “barbarians” and “polis.” The term “barbarian,” derived from the Greek word “βάρβαρος,” originally referred to non-Greek-speaking peoples and later came to denote those perceived as uncivilized. The word “polis” (ἡ πόλις), meaning “city-state,” signifies the independent political entities that composed Greece. These city-states, each with unique forms of governance, engaged in intricate diplomatic interactions that significantly shaped their collective history.

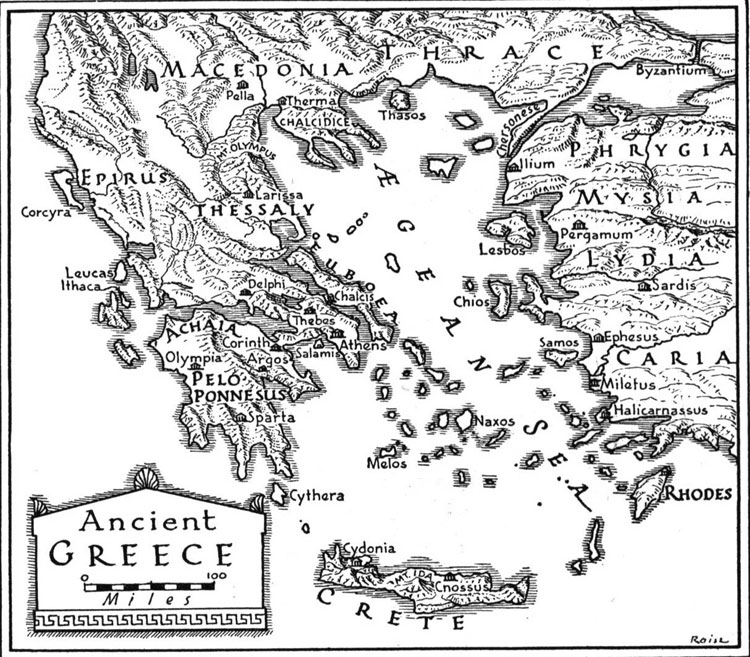

Map of Ancient Greece – GREEKA.com

Ancient Greece was not a unified nation but a collection of city-states (polis), each functioning as an independent entity. These city-states varied greatly in size, population, and political organization. While some, like Athens, adopted democratic governance, others, such as Sparta, operated under oligarchic or monarchical systems. The prevalent form of governance among the city-states was the patriarchal kingdom. Despite their frequent conflicts, these city-states shared cultural and linguistic ties that facilitated diplomatic engagements.

Diplomatic Practices and Alliances

Diplomacy in ancient Greece was characterized by both cooperation and conflict. City-states often formed alliances to counter common threats or achieve mutual goals. However, these alliances were frequently temporary and shifted based on the changing political landscape. For example, during the Persian Wars, city-states like Athens and Sparta, typically adversaries, united against the Persian Empire. This cooperation culminated in significant victories at the battles of Marathon (490 BCE) and Salamis (480 BCE), which were instrumental in repelling the Persian invasion.

The Greek alliance, known as the Hellenic League, was formalized by a treaty between the Athenian Archon Themistocles and the Spartan King Pausanias in 481 BCE. This treaty underscored the potential for unity among the Greek city-states in the face of external threats. The subsequent Peace of Callias in 449 BCE, negotiated by Pericles, marked the end of hostilities with Persia and established terms favourable to Athens, highlighting the effectiveness of Greek diplomatic efforts.

The Role of Ambassadors and Messengers

Greek diplomacy was marked by the formalization of the role of ambassadors and messengers. The term “kerux” (κήρυξ), meaning “herald” or “messenger,” referred to individuals tasked with delivering messages between city-states. These messengers often depicted carrying a distinctive staff, enjoyed diplomatic immunity, emphasizing the sacred nature of their role. The concept of the “diploma,” a document made of papyrus containing official messages, is the etymological root of the modern term “diplomacy.”

In Homer’s Iliad, Talthybius is depicted as the first messenger, illustrating the early importance of this role in Greek society. The messengers’ duties were strictly limited to conveying messages; they were not authorized to engage in negotiations or add personal commentary. The Greek belief in the divine protection of messengers, associated with the gods Hermes and Talthybius, further reinforced the inviolability of their mission.

Political Intrigues and Internal Diplomacy

Internal diplomacy within city-states was equally complex. Greek city-states were often internally divided by political factions with differing views on governance and foreign policy. These factions engaged in secret alliances and power struggles, influencing both domestic and foreign policies. For instance, during the Peloponnesian War, internal political dynamics within Athens and Sparta significantly impacted their strategies and alliances.

The Macedonian Unification

The fragmented nature of the Greek city-states presented both opportunities and challenges. The Persian Empire, aware of the Greeks’ disunity, often exploited these divisions to maintain influence in the region. However, the vision of a unified Greek world was eventually pursued by Macedonian leaders. King Philip II of Macedon sought to unite the Greek city-states under his leadership, ostensibly to liberate Greeks under Persian rule. This vision was realized by his son, Alexander the Great, whose conquests extended Greek influence across three continents.

The diplomatic practices of ancient Greece were foundational in the development of international relations. The interplay between conflict and cooperation among the Greek city-states fostered a rich tradition of diplomacy that influenced subsequent civilizations. The Greek emphasis on formalized roles for ambassadors, the strategic use of alliances, and the engagement in complex internal diplomacy underscore the sophistication of their diplomatic efforts. This legacy of Greek diplomacy, characterized by both innovation and pragmatism, continues to be a subject of study and admiration in the annals of history.

Leave a comment